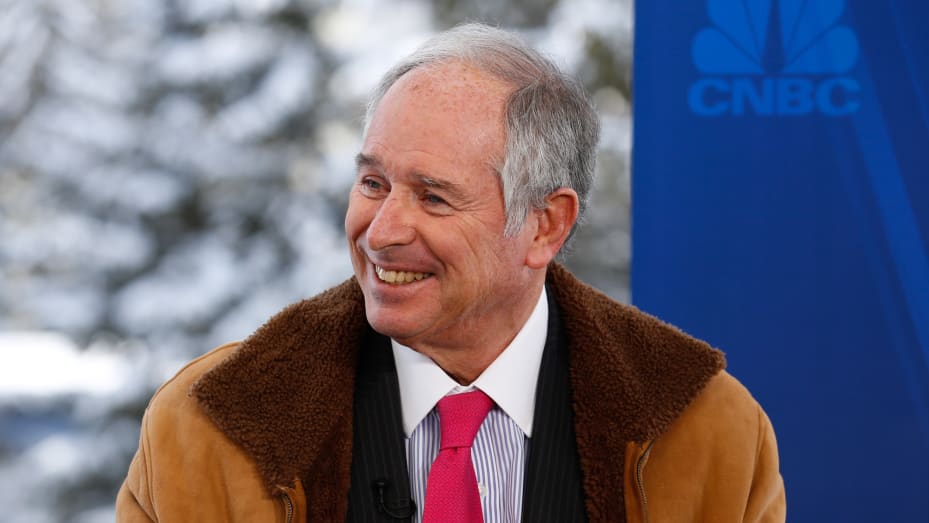

These are the investment tips from Steve Schwarzman, the billionaire co-founder of Blackstone

Steve Schwarzman’s guiding philosophy has always been to «go big,» and even though Blackstone has surpassed $1 trillion in assets, it still feels expansive.

The 77-year-old founder and CEO of Blackstone grew up in a Philadelphia suburb. From the age of ten, he worked in his father’s curtain and bedding store, helping at the counter. At 14, he already had his own lawn-mowing business , where he focused on new clients while his younger twin brothers mowed the lawn. His desire to succeed began early. In his book What It Takes (Avid Reader Press: 2019), he recalls pleading with his father to expand her successful fabric store nationwide (“We Could Be Like Sears”) or even in the state of Pennsylvania. His father refused, saying: “I am a very happy man. We have a nice house. We have two cars. I have enough money to send you and your brothers to college. What more do I need?

Steve Schwarzman , who studied at Yale University, has made up for his father’s lack of ambition. Since he founded Blackstone in 1985 with the late Pete Petersen, Blackstone is today the world’s largest alternative asset manager , with more than $1 trillion in assets. Forbes estimates Schwarzman’s net worth at $39 billion and his company has made several billionaires, including its current president, Jonathan Gray, with a fortune of $7.6 billion. Although Blackstone began as a traditional leveraged buyout operation, it has evolved into a buy-and-build company, including innovative financing techniques that have indefinitely extended fund maturities and made the business, which is typically a club , be easier for retail investors. Real estate is a huge business for Blackstone . It currently owns more than 12,000 properties in its $300 billion commercial real estate portfolio. In Europe, it is the largest owner of warehouses and logistics facilities . [For more information about the company, read Blackstone’s strategy to ‘conquer the world’ and become the global leader in private equity ].

Forbes (F). How did you get started in the investment business?

Steve Schwarzman (SS). I got into venture capital investing, representing some of the companies that had just started. At that time there were only eight to ten venture capital companies. I ran the mergers and acquisitions group at Lehman Brothers, advising on private equity transactions, where I spent a total of thirteen years and became CEO. The people in this small, nascent world of private equity [editorial note: then known as leveraged buyouts], were more or less my age mates, so I knew them socially. People were reluctant to represent them because the operations they did were very small and the whole concept was new. For me it was something natural, because I knew the people. And so I was able to see how the operations were set up because I advised them: that was my beginning. And then in 1982, I wanted to get Lehman Brothers into that business because I thought we could raise a lot more money as one of the largest investment firms in the world. Lehman’s executive committee refused to get into the venture capital business, which I think was a costly decision on their part.

F. How has your investment strategy changed throughout your career?

H.H. Well, the world has changed radically since we started in 1985. Now it’s not just about venture capital, but even venture capital is divided into different sub-asset classes. Companies like ours were the pioneers in entering other alternative asset classes, such as real estate, hedge funds and credit. We now have 72 different strategies to invest in, and when we started, there was only one. As time has passed, the world has changed and it made more sense to diversify and add new strategies. But we never saw it as diversification. We looked at it as different things that were cyclically undervalued and getting into that area would do a great job for our initial customers who are in other products. So people unfamiliar with what we were doing and why we were doing it thought we were diversified. We felt like we were doing something that was absolutely wonderful. That’s one of the reasons we ended up being successful at almost everything we did and why other people who tried to emulate our strategy often entered those lines of business at a time when those areas were overvalued or unavailable. attracting really great people who had domain knowledge in that area.

F. What investment would you consider your company’s greatest triumph over the years?

H.H. One of the most notable was our investment in Hilton, which we made in early July 2007, absolutely at the height of equities. And we knew we were paying a high price for it, but we believed there were at least two notable opportunities to increase Hilton’s profits. The first is that Hilton had not expanded internationally for at least two decades. And so it had the number one name at the time internationally, but it had aging hotels and no new ones. We thought that if we aggressively opened new hotels, did it from the standpoint of a management company, and got other people to put up the capital, we could probably increase profits, just from that activity, by about $500 million a year. . The second opportunity was that Hilton ran an operation with three headquarters and three full staff, a company doesn’t need to do that, it can be done with one. So we thought the opportunity for efficiencies was also in the area of $500 million. When we bought the company, even though we paid what seemed like a significant price, we thought the price was pretty good, right? Because we knew what we thought could be achieved relatively easily and it turned out to be true.

Meanwhile, we had the global financial crisis, which reduced the business’s profits by about $500 million. It’s funny, these numbers are more or less the same. So we put more money into the business to make sure it was safe, but the natural rebound in the economy, plus that extra billion dollars of profits – as well as continued growth throughout our tenure and better management of existing properties – gave us a total return benefit of $14 billion, which was a great result.

F. On the other hand, could you name an investment that has disappointed you and from which you have learned something?

H.H. Clear. I would say that more than a disappointment, a disaster. It was Edgcomb Steel, the third investment we made in 1989. It was a steel distribution business. Everything went wrong in that operation. Our analysis was wrong. One of our partners thought it was simply about making money off of inventory profits. In other words, steel prices kept going up and all that. We had inventory, whatever we paid for it, it happened to be worth a lot, so that went into your income statement. When steel prices go down, the opposite happens, right? When steel prices fell, the company’s profits plummeted and it struggled to meet its debt maturities. We put more money into the company to save it, but it continued to go poorly. Then I realized that the only way out was to sell the business, which we did in 1990, to a large steel company in France. We lost 100% of our original investment, although we saved the money we put in the second time. It was a completely traumatic experience. I was the person who made the final decision to make the deal, so it was my mistake and I realized that we couldn’t make another mistake like that again.

So we redesigned the way the firm made decisions, instead of relying solely on me. From now on, all the company’s partners would participate in each decision in a very formal process, instead of the informal one we had before. All risk factors had to be listed and discussed thoroughly among partners. A simple rule is that everyone at the table had to discuss the possible weaknesses of the trade and the scenario in which it could lose money. We adopted that process for basically everything we do and what we achieved was to depersonalize decision making. People were trained to always worry about what could go wrong, not just what could go right, and so, ironically, Edgcomb became the most important investment we ever made – despite the pain of going through it – because It changed the company from a learning perspective instantly.

F. What would you say are the most important parameters that an investor should take into account? Which factors, macro or microeconomic, do you pay more attention to?

H.H. You have to understand the macroeconomic environment in which you invest, which helps control the price and return expectations of the investment at a microeconomic level. First, we look at what the general drivers of this company’s success are. And we look for what we call good neighborhoods, where it looks like there’s built-in growth for that industry and for that company. Let’s hope it is not particularly subject to economic cycles. An example of this is the AI revolution with data centers, where we currently have the largest share in the world in terms of building data centers for AI. So we identified that trend three years ago, before ChatGPT, and now a company we bought three years ago – QTS – has grown six times since then (Blackstone acquired QTS, which operates data center leases, for about $10 billion ago three years in what was the largest data center transaction in history at the time). Another important aspect we analyze is whether the company can expand geographically. With data centers and so on, that’s happening as we speak. So we’re really looking for growth tracks for both the company and the industry, as well as geographic expansion.

F. If you could give your twenty-year-old self one piece of investing advice, what would it be?

H.H. Surround yourself with the smartest people you can find and create a system that generates huge first-party data. Be patient. Don’t force an investment decision: invest only when you have enormous confidence that something will work. I know that the way my brain works, I need a lot of information to be able to see trends and understand things. The more information I have, the easier it is for me to make a decision. Some people can just sit in a room and read annual reports or think big thoughts. I’ve always needed to have a lot of current information to think about, and then I tend to be able to see patterns in that data. If there is no data, it is difficult to see patterns.

F. Are there any investment ideas or themes that you think are especially appropriate for today’s investors?

H.H. There are two or three things. Credit remains an extremely good sector from a risk/return perspective. The real estate sector is beginning to see a change in its economic cycle because construction in almost all asset classes has decreased significantly. And as for private equity, it is going to be much more active when interest rates start to fall at the end of this year; I think around the third or fourth quarter, but we could be surprised a little earlier.

F. What would you say are the biggest risks facing investors today, either from a broad strategy standpoint or from the current environment standpoint?

H.H. The biggest risk is the current geopolitical environment. The second is regulatory concerns, while the third is political uncertainty. We have a real trend since the current administration in which we have seen an exponential increase in regulation in almost all areas. Over time, this type of approach has a negative impact on economic growth.

F. What book would you recommend to all investors to read?

H.H. You could read my book What It Takes , which has become a bestseller. People talk to me about him all the time all over the world and it always surprises me that they do. It seems like it has had a big impact on a lot of people. I don’t read too many business books because I spend a lot of time on that activity. One of the good books I read recently and liked was Shoe Dog , Phil Knight’s memoir about Nike. It was interesting to learn about his struggle to start the company. I’m always reading several books at the same time.

F. Thanks, Steve.