With assets valued at R$9 billion, Walter Kortschak was one of the first to invest in several companies that are now public, such as Robinhood, Twitter and Lyft

Billionaire investor Walter Kortschak is confident in his formula for success: “Investing is about duration and persistence ,” he says. “I don’t know many people in this industry who have done early-stage investing, growth equity and private equity and done it well, for this long, consistently,” Kortschak, 65, told Forbes.

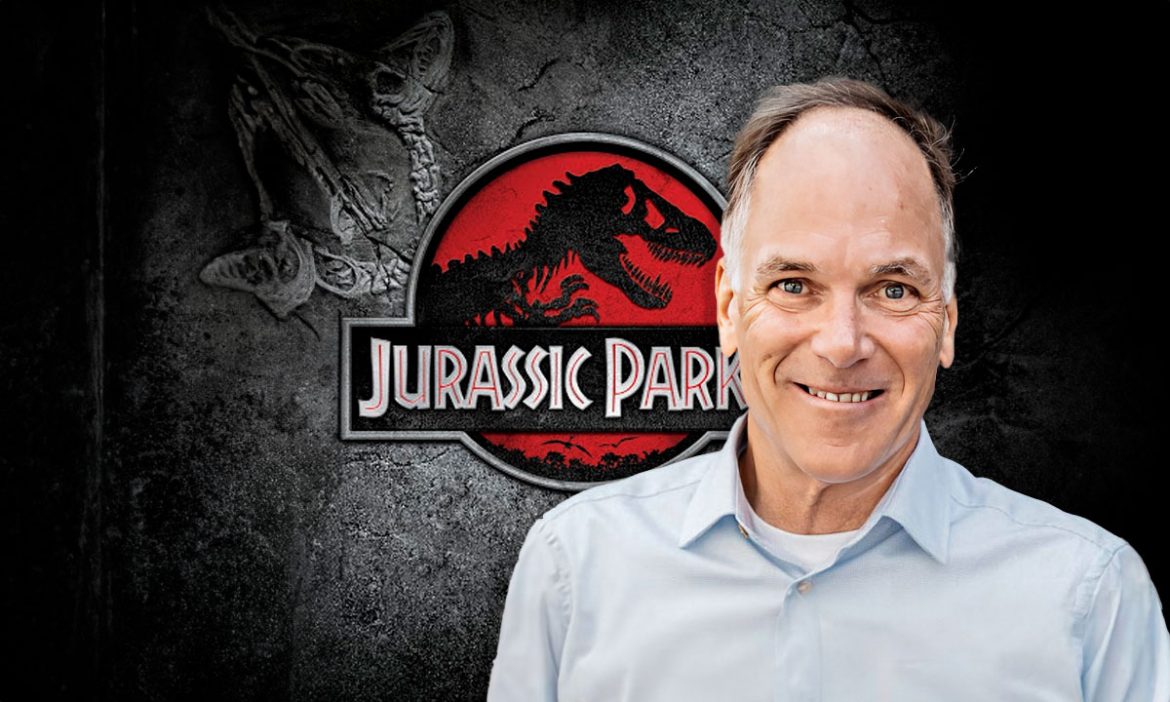

The seasoned investor owns homes in Aspen and London, as well as a 1,000-acre plot of land on the island of Kauai. He acquired most of his land in Hawaii, where the Jurassic Park franchise was filmed and near Mark Zuckerberg’s estate , in 2003.

Today, Kortschak’s assets are valued at around $1.6 billion , thanks to his time at growth equity firm Summit Partners and, later, his personal investments in early-stage companies that yielded big returns.

The trajectory of billionaire Walter Kortschak

Born in Canada to an Austrian father and an American mother, Kortschak had an international childhood, growing up largely in Geneva, as his father worked for the Swiss branch of chemical manufacturer DuPont.

Kortschak initially wanted to be a software engineer and earned two degrees in the field: a bachelor’s degree from Oregon State University and a master’s degree from Caltech.

He then joined a computer startup in 1982, which later became MSC Software. A few years later, he returned to business school at UCLA, where he was one of two Venture Fellows in 1985. Through the fellowship program, which places students to work at venture capital firms during the summer, Kortschak interned at Crosspoint Venture Partners, an early-stage investment firm. He joined Crosspoint full-time in 1986, a difficult time to break into venture capital. He says there were “probably eight” associate positions in the entire industry that year.

Kortschak left Crosspoint and joined Summit Partners in 1989 to focus on investing in later-stage, profitable, growth-stage companies, primarily in the technology sector. At the time, Summit was a five-year-old firm with $400 million under management, and Kortschak was tasked with opening the firm’s West Coast office, based in Boston. One of his first major investments was in security company McAfee in 1991, which went public just a year later, yielding a 9x return for Summit.

During his two decades at the company, Kortschak made a name for himself, appearing on Forbes’ Midas List —the list of the world’s top venture capitalists—from 2005 to 2009. He was involved in many of Summit’s technology investments and acquisitions, including computational optics company E-Tek Dynamics (with a 61x return) and data networking company Xylan (with a 127x return).

He stepped down from his active role at Summit in 2010, when the company had surpassed $5 billion in assets, and became an angel investor and advisor, a role he still holds today.

Solo career

With decades of experience under his belt, the billionaire decided to go solo and return to early-stage investing.

Through Firestreak Ventures, Kortschak invests in machine learning infrastructure and developer-facing companies, and with Kortschak Investments, he invests in growth-stage software, healthcare, fintech, and clean energy companies.

Kortschak was an early investor in several companies that are now public, including The Trade Desk, Lyft, Palantir, Robinhood and Twitter. He’s now also betting on AI, with stakes in OpenAI and Anthropic, among others.

He says his investing career has indeed come full circle — from early stage to growth capital and now back to early stage — although this time the types of companies are different.

Check out highlights from billionaire investor Walter Kortschak’s interview with Forbes below:

Forbes: Is there a current investment idea or theme that you think is most important today?

Walter Kortschak: I believe that investors, regardless of stage, need to carefully consider the amount of capital needed to bring a company to breakeven. We are facing financial market conditions that are not favorable for IPOs, and a mergers and acquisitions (M&A) market that has been increasingly selective and shrinking for some time.

Investors need to be patient as their investments will remain private for longer and have fewer opportunities for liquidity. As a result, the onus is now on the venture capital investor to help their companies achieve profitability and balance this with revenue growth, but in a capital-efficient manner.

The most talked about exit route today is through private equity, but these buyers tend to be conservative in their pricing and generally don’t overpay, and they don’t like to finance operating losses. The more capital invested, the harder it is to create alignment between management and investors.

Speaking of industries, obviously everyone is focused on AI. It’s a bit of a gold rush right now. Many use cases will be automated by AI and powered by applications built on top of closed models like OpenAI or open source models. In the short term, the results of AI investments may disappoint, but in the long term, the impact of AI on virtually every industry will be profound. My personal advice is to be selective, invest in outlier founders, and be disciplined in the number of investments you make and the capital you allocate to manage risk exposure.

What is the biggest risk investors face today, either from a broad strategy perspective or from the current investment environment?

FOMO, or fear of missing out. Trying to win deals that everyone wants to win, essentially the “hot deals”. The risk is that investors become desperate, especially when they have recently lost a competitive bid. Hence FOMO. Investors then tend to over-invest in a sector at any cost and take shortcuts.

The other strategy is called “truffle hunting,” which involves a more deliberate and patient approach to identifying undervalued opportunities in sectors that other investors aren’t looking at. This strategy requires considerable industry expertise, so talking to founders, investors, and industry experts, as well as mapping out the landscape, is key. Both strategies work. It’s just a matter of having the discipline to not get caught up in the mass hysteria of a sector.

What investment do you consider your greatest triumph?

My largest investment at Summit was E-tek Dynamics. E-tek was a pioneer in the optical components industry. I first called the founder, Theresa Pan, directly in 1996. She and her husband, JJ Pan, ran E-tek for over 14 years, growing the business to over $30 million in revenue and achieving profitability.

They were looking to diversify their equity and bring in a team to help the company grow. I spent a year convincing Theresa to join Summit instead of selling the business to Corning. In 1997, she and her husband agreed to sell 60 percent of the company to Summit for $120 million. I became president, and part of the plan was to help her step back from the company so she could spend more time with her teenage daughter. We recruited a CEO, Michael Fitzpatrick, as part of a succession strategy and assembled a world-class management team. The new team diversified the company’s product line into integrated optical subsystems, which became a valuable commodity for telecommunications providers building fiber-optic infrastructure. The company completed an IPO in 1998, followed by several follow-on offerings, two acquisitions, and finally sold to JDS Uniphase for $18.4 billion in 2000, in one of the largest technology mergers in history. Summit invested $108 million in 1997 and returned $4.2 billion, generating a 40x multiple on cost and an IRR of 350%.

My biggest angel investment was in The Trade Desk (TTD) in 2012. TTD is a demand-side programmatic advertising platform. I was introduced to the company through my investor network in Southern California and was impressed by the founder, Jeff Green, and his big vision for the company. We share the same philosophy of raising the least amount of money necessary to achieve profitability. I invested $367,000 in the Series A round in 2012 for 2% of the company, or a valuation of $18.75 million. The company IPO’d in 2016 and now has a market cap of nearly $50 billion. My adjusted holding became 6.66 million shares, and with the stock price at $90, that values the investment at about $600 million, or a 1,600x multiple of cost.

What investment do you consider your biggest disappointment and what did you learn from it?

Without revealing any names, one of my personal investments was completed in 2015. The company raised a lot of capital during the height of the funding bubble in 2018, at a very high valuation. The capital gave the company carte blanche to expand the business in multiple directions. It’s hard enough to build a startup focused on solving one problem, but it’s nearly impossible to build three distinct businesses, just too many distractions. What I learned: It’s dangerous to overcapitalize a young company, and the combination of a capital-intensive business with relatively low gross margins is very difficult to overcome.

What have you learned from some of your mentors?

Go into a meeting with a prepared mind and be ready to make your case. Have an opinion. Also, remember that venture capital investing is as much about getting in as it is about getting out. Few in our industry are skilled at doing both. Those who are become legends in our field.

Books you recommend to every investor?

“Bad Blood” by John Carreyrou. This is the book about Theranos, the blood-testing startup and its founder and CEO, Elizabeth Holmes, which became the biggest corporate fraud case since Enron. For me, this book was a wake-up call for employees, investors, board members and even corporate partners.

“The Innovator’s Dilemma” by Clayton Christensen. He talks about why certain market-leading companies become vulnerable to startups when they become complacent and risk-averse. This resonated a lot with me, especially from my experience as an investor in Diamond Multimedia Systems, which was challenged by Nvidia.