Jimmy Rane took over a tiny treated-lumber business and used his showman flair for marketing to transform it into a major player. The Yella Fella of Abbeville is now Alabama’s only billionaire—and the lumberyard will never be the same

«You know what that means?” Jimmy Rane, the 76-year-old founder and CEO of Great Southern Wood Preserving, a lumber treating outfit, asks with a chuckle, picking up an axe in his Abbeville, Alabama, office and pointing at the letters GATA inscribed down its handle. “It means ‘get after their ass.’ And you’ll see that motto in every Great Southern building.”

The mantra was originally intended to fire up Georgia Southern University football fans back in the 1980s. Rane’s co-opting of the phrase is just one way the lifelong Alabama resident has tried to marry the public’s perception of his business to the South’s second-most-popular religion: College football.

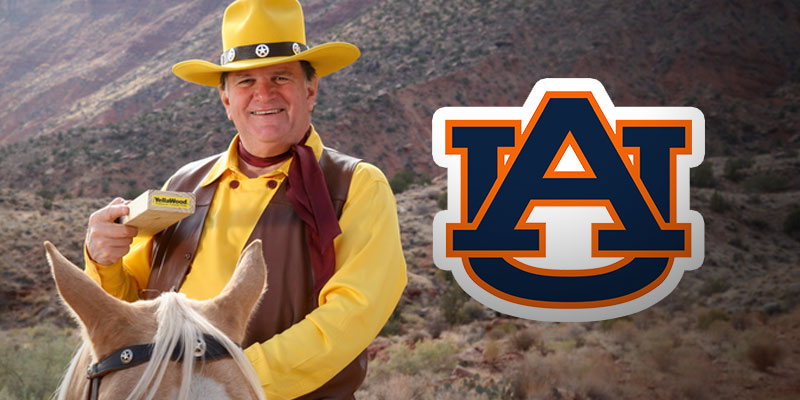

From the mid-1980s through the ’90s, he sponsored several NCAA teams and hired nearly 20 college football coaches as pitchmen, including Florida State’s Bobby Bowden (d. 2021) and Auburn’s Tommy Tuberville. He even put two coaches on his company’s board: Auburn’s Pat Dye (d. 2020) and Alabama’s Gene Stallings. Rane has a 1989 Southeastern Conference Championship ring of his own, thanks to his role as financial booster—and later a trustee—of Auburn, his alma mater.

The marketing blitz doesn’t stop with NCAA Division I football. Rane also has an alter ego: The “Yella Fella,” a crime-fighting cowboy he portrayed in TV commercials throughout the South from 2004 to 2012. Each ad was structured as an “episode” during the last four “seasons,” complete with a cliffhanger, keeping viewers hooked. (The Yella Fella has since been replaced in ads by a team of clever beavers.)

All the sizzle serves a simple service: Building a brand around a commodity product. Rane was inspired by a case study he read during a short course at Harvard Business School about Frank Perdue’s successful effort in the 1970s to brand chickens (tagline: “It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken”). If possible, Rane had an even harder job than Perdue: Forging a recognisable brand in one of the world’s most commodified industries, lumber treating—the process of applying preservatives to pre-cut, raw lumber to ensure it lasts a “lifetime,” as Great Southern’s YellaWood proudly proclaims.

Rane took over what became Great Southern in 1970, when the owners—his first wife’s parents—died in a car crash. It wasn’t much: A near-bankrupt backyard lumber treating plant with just $163,000 in sales (adjusted for inflation). But 53 years later, largely thanks to Rane’s marketing genius, Great Southern is a $2 billion (2022 revenue) company with some 1,900 employees and 15 treating facilities in 12 states. Forbes calculates that he’s worth $1.2 billion—all but $200 million of it attributable to his 100 percent stake in Great Southern—making him Alabama’s only living billionaire. (The state’s first billionaire, construction heiress Marguerite Harbert, dropped from the ranks in 2012 before dying three years later.)

The treated lumber industry is highly fragmented, with many privately owned operators. Even the most seasoned industry observers struggle to quantify the size of the market or any specific firm’s share. But four publicly traded companies are among its largest treaters. The biggest is Grand Rapids, Michigan–based UFP Industries, with $9.6 billion in 2022 revenue; it makes non-wood composites and packaging in addition to treating wood. Next are Montreal’s Stella-Jones, Vancouver-based Doman Building Materials and Pittsburgh’s Koppers Holdings. Like the Yella Fella, each has about $2 billion in revenue.

Great Southern has net margins in the 4 percent to 7 percent range—roughly in line with those of its public competitors. It’s a competitive business, but Great Southern has a degree of incremental purchasing power thanks to its size, says DA Davidson analyst Kurt Yinger. The fact that Great Southern manages to post numbers in line with its public rivals is an accomplishment given its comparative lack of ready access to capital.

Keeping costs low is also key. That’s what makes the company’s army of market analysts, easily mistaken for a Wall Street trading desk, so important. With conversations muffled by soundproof walls, each analyst hits the phone while scanning multiple computer screens, collecting trade and quote data to forecast pricing at the supplier plants where Great Southern buys its lumber, so that the company can fight for every dollar.

In this sort of ultracompetitive commodity business, smart marketing can make a big difference. “In the 1980s and 1990s, nearly all of the pressure-treated wood for residential applications was treated with the same preservative, and all the wood—with a dull greenish tint—looked the same,” says Building Products Digest Editor David Koenig. “Great Southern had the foresight to invent its own YellaWood brand and to add bright yellow tags [to the wood it treated] that took the focus off the green wood and added the air of a premium product.”

Says Rane: “I think marketing played a major role, because we were really struggling to grow in the early 1980s, and when I’d try to talk to a buyer about the quality of our lumber or the purity of our chemicals, the first and last question they’d ask was ‘What’s your price?”

Rane could have moved his business to a big city like Atlanta or Houston in return for tax breaks, but he’s chosen to keep his headquarters in Abbeville, the town of 2,000 where he grew up. It owes much of its postwar prosperity to Rane’s entrepreneurial father, “Mr Tony,” who died in 2011. Mr Tony was president of the Chamber of Commerce, owned several businesses in town— including the Village Inn Restaurant and Rane Furniture—and was credited with persuading New England textile giant Pepperell Manufacturing to open a plant there in the 1950s. The plant, which employed more than 1,300 at its peak and made bedsheets and pillowcases, closed in 2007. “If you drove through Abbeville in 1998, you’d lock the door and keep going,” Rane says. “There were burned-out buildings, no trees and broken sidewalks.”

Over the years, Rane has spent millions of dollars restoring Abbeville to its 1950s glory. To get a table at Huggin’ Molly’s diner, named for a local ghost, customers pass through a drugstore built in 1926. The pharmacy was shipped to Abbeville from California in 2005, and the counter is topped with an exact replica of Mr Gower’s soda fountain from It’s a Wonderful Life. Great Southern’s marketing team works inside the last restored “castle-style” Sinclair gas station in Alabama.

The town is also the site of “YellaWood University,” a weeklong retreat for promising young employees, many of whom bunk in the former homes of Rane’s childhood friends (Great Southern owns the houses now). “Harvard teaches that your best leadership is grown from within, and that’s so true, because we’ve had very little success hiring from the outside,” Rane says.

While the company’s heart, soul and headquarters have remained in Abbeville, its operations have expanded well beyond. Great Southern took advantage of the Great Recession to acquire seven treating plants throughout the eastern U.S. between 2007 and 2012, doubling its footprint to 14 facilities in 12 states. A 15th plant was added in 2021. That helped endear the company to major customers like Home Depot, who value regional suppliers, and set the stage for a period of record growth. Sales have more than doubled from $880 million in 2016, thanks in large part to the pandemic, which sent lumber prices soaring as stuck-at-home folks remodeled and renovated.

It’s a far cry from the earliest days, when Rane was still treating the wood himself and the company was “completely busted.” Back in 1971, in need of a lifeline, he asked the Bank of Abbeville for a $5,000 loan. “I walked in there in my coveralls, nasty as hell,” Rane remembers. “The banker told me, ‘You’re going to ruin your life.’ But he knew if he turned me down, he was going to end up with a treating plant.” Seems like things turned out all right for both of them.